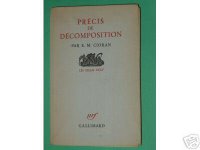

It’s always fascinating to witness the arrival of book that doesn’t exist. The publication of Exercises négatifs, which was E.M. Cioran’s original title for the manuscript that later became Précis de Décomposition (his first book to be written in french and doubtlessly his best known), amounts to an important event, an indication of the growing popularity of this Roumanian-born writer. Just ten years after his death, his readers (or leastwise his publishers) have such an appetite for new works beyond the fifteen that he published during his lifetime (which had already been followed in 1997 by the excellent one-thousand pages of his Cahiers 1957-1972). Clearly, despair and elegance are still greatly appealing these days.

It’s always fascinating to witness the arrival of book that doesn’t exist. The publication of Exercises négatifs, which was E.M. Cioran’s original title for the manuscript that later became Précis de Décomposition (his first book to be written in french and doubtlessly his best known), amounts to an important event, an indication of the growing popularity of this Roumanian-born writer. Just ten years after his death, his readers (or leastwise his publishers) have such an appetite for new works beyond the fifteen that he published during his lifetime (which had already been followed in 1997 by the excellent one-thousand pages of his Cahiers 1957-1972). Clearly, despair and elegance are still greatly appealing these days.A Warning

But the celebration is somewhat spoiled and our pleasure diminished. The problem arises primarily from the choice of a title – Exercise négatifs – that leads us to expect something that this publication does not, in fact, offer. What we do find is a collection of a certain number of unfinished passages that Cioran had included in his first version of Précis before deciding to delete them as work on this book progressed. In other words, we don’t (except for a group of passages that are gathered together in a chapter entitled “Variantes définitives”) find first-drafts of published texts or, for that matter, subsequent drafts. The title Exercises négatifs should, rightly, designate the first version of Précis as a whole. In point of fact, however, its use for the present publication suggests that it was a different book altogether, written apart from Précis, even though the real “Exercises négatifs” are the Précis in its embryonic form. In addition to this problem, the order in which the passages themselves are presented is regrettable. The editor has adopted the classification established by the Bibliothèque Littéraire Jacques Doucet, which is not, unfortunately, the one chosen by Cioran himself for the numbering of his texts.

In spite of its title, then, this volume does not really offer us Cioran’s Exercises négatifs; such is the warning that we do not receive from Ingrid Astier, who edited, introduced, and annotated this volume. These criticisms may seem like quibbles, but it is nevertheless true (think of Pascal’s Pensées) that unfinished work requires certain editorial precautions.

Exclamations of a Reprobate

These cavils aside (I expect that future editions will clarify things, even at the risk of confusing them even further…), the transcription and the publication of these manuscripts have the great merit of allowing us to read what Cioran deemed unworthy of being read, passages that he himself censured. These vigorous first drafts, supplemented by a chapter entitled “Vers les syllogismes de l’amertume”, overflow with vehement paragraphs : Cioran’s first, impetuous spurts, which are, indeed, excessive in their content. Their style, although not excessively awkward, has yet to undergo its later refinements.

Précis ; provocative statements on such themes as hope, love, and marriage (“a spasm blessed by the mayor and the priest”) ; anecdotes, alternating between the grotesque and the burlesque, of a metaphysician immersed, in spite of himself, in a vulgar world (a “Hamlet amidst the dressmakers” who, at a dance, reflects that “the hatred that one reads in the eyes of young girls whom no one has asked for a dance terrifies me more than does an operating room”); declarations of war against literary critics and, even more, against professors (whom he describes as “reading machines that transform the solitude of a few exceptional spirits into commodities for idiots”) ; lengthy flights around the theme of suicide, whose deletion from the Précis suggests, not that the somber moralist had a moral philosophy (!), but that he recognized the weakness of the idea that the thought of suicide was superior to suicide itself (“Suicide as a means of knowledge,” “Enlivening death,” etc.). Above all, one finds, in page after page, the aggressive skepticism of a thinker who has given up his earlier political enthusiasms and who invites us all (this is in 1946) to give up our certitudes as he did, to fight against all ideologies, and to imitate, if not the sage’s indifference, at least the philosopher’s doubt.

Précis ; provocative statements on such themes as hope, love, and marriage (“a spasm blessed by the mayor and the priest”) ; anecdotes, alternating between the grotesque and the burlesque, of a metaphysician immersed, in spite of himself, in a vulgar world (a “Hamlet amidst the dressmakers” who, at a dance, reflects that “the hatred that one reads in the eyes of young girls whom no one has asked for a dance terrifies me more than does an operating room”); declarations of war against literary critics and, even more, against professors (whom he describes as “reading machines that transform the solitude of a few exceptional spirits into commodities for idiots”) ; lengthy flights around the theme of suicide, whose deletion from the Précis suggests, not that the somber moralist had a moral philosophy (!), but that he recognized the weakness of the idea that the thought of suicide was superior to suicide itself (“Suicide as a means of knowledge,” “Enlivening death,” etc.). Above all, one finds, in page after page, the aggressive skepticism of a thinker who has given up his earlier political enthusiasms and who invites us all (this is in 1946) to give up our certitudes as he did, to fight against all ideologies, and to imitate, if not the sage’s indifference, at least the philosopher’s doubt.Beyond the obsession with death and Cioran’s trademark skepticism, the reader is struck by the “histrionic” triteness of some passages, which is only the bitter farce, bad intentions, idle fulminations, and abusive caricatures of a picturesque misanthrope.

All of this is not the best Cioran, or the most subtle, or the most poetic – but it is, to be sure, the most furious ; it is also continuously excellent. These one hundred and fifty rich, “unpublished” pages offer rewarding hours to their intrepid readers, including the philosophers among them (“The vogue of death in contemporary philosophy”), the historians (“Europe, a carrion-ridden land”), and writers (passages on the great Roumanian poet Eminescu and on “The importance of wickedness”).

A Wicked, Despairing Misanthrope

These chapters, which Cioran had rejected, should not diminish the growing world-wide reputation of this “écrivain maudit” who was born in a peaceful Transylvanian village. More than the purified style to come, these “trompe l’oeil” Exercises négatifs reveal the passionate, indeed the explosive temperament of Cioran with pen in hand. Although Ingrid Astier’s postface begins by quoting George Perros’s mitigating idea that “there cannot be a despairing work since the motive that gave birth to it is affirmative” and concludes with uplifting remarks about the author’s “fundamental respect for human beings,” Cioran does not seem to be especially full of hope when, for example, he says: “Any philosophy that sets out with the intention of finding reasons for hope is, by that very fact, forever disqualified” or “Has one ever heard a hopeful song that does not arouse a slight feeling of disgust?” Cioran, who was so elegant, shows himself here as also decidedly disrespectful, spiteful, and devilishly embittered. This is because, as he says, “Everyone has his model; I need one that is scornful, wicked, and lucid.”

Nicolas Cavaillès

Translated by Thomas Cousineau

October 2005

Extases frelatées - En marge du Précis de Décomposition

Nicolas Cavaillès